Garbage in Sri Lanka

An Overview of Solid Waste Management in the Ja-Ela Area

Levien van Zon (levien@scum.org)

Nalaka Siriwardena

October 2000

Integrated Resources Management Programme in Wetlands (IRMP), Sri Lanka

Free University of Amsterdam (VU) / Institute for Environmental Studies

(IVM), The Netherlands

http://environmental.scum.org/slwaste/

Files available for downloading:

Both PDF-files were meant for double-sided printing or on-screen viewing.

For a summary of the report including full conclusions &

recommendations and references, see below. The acronyms used in the report

are listed here.

Summary

1. Introduction

1.1 About this survey

The aim of this survey is to describe the various aspects of solid waste

and its management in the Ja-Ela Divisional Secretary (DS) division, and

to investigate the possibility of a participative community project in

waste-management under the Integrated Resources Management Programme in

Wetlands (IRMP).

1.2 IRMP

IRMP is a five-year project of the Central Environmental Authority (CEA),

which currently operates in the wetland area of Muthurajawela Marsh and

Negombo Lagoon. It aims to develop a workable model for participative and

integrated management of wetlands in Sri Lanka. Activities are first run

as pilot projects, to see whether they work and how they can best be implemented.

1.3 The area

The Ja-Ela DS Division lies in the Gampaha District of the Western Province,

and is located just north of Colombo. It covers some 65 km2,

has about 190,000 inhabitants, and is subdivided into the Pradeshiya Sabha

(PS) areas of Kandana, Ragama, Batuwatta and Dandugama, and the Ja-Ela

Urban Council (UC) area. Both its population density and population growth

are relatively high. A small strip on the western side of the division

is part of the Muthurajawela Marsh.

1.4 The waste problem

Infrastructure and resources for waste collection are lacking in most parts

of the country, so uncontrolled scattering and dumping of garbage is widespread.

There are no proper facilities for final disposal of most of the solid

waste produced by households and industries. Waste that is improperly dumped

can impede water-flow in drainage channels, and provides breeding places

for disease vectors such as rats and mosquitoes. Open dumping sites in

natural areas cause pollution of ground- and surface-water, and will facilitate

encroachment. Open burning of waste at low temperatures is also widespread.

It contributes to atmospheric pollution and may cause serious health problems.

1.5 Government organisation

The government levels in Sri Lanka include the National Government (the

President, Parliament, and the Ministries and their departments, agencies,

boards, etc.), Provinces (headed by Provincial Councils), Districts (headed

by a Government Agent), Divisions (headed by a Divisional Secretary), Pradeshiya

Sabhas (PS) and Municipal and Urban Councils (MC and UC), and Grama Seva

Nildaris (GN). The PS, MC and UC are assigned a Public Health Inspector

(PHI) by the Ministry of Health, who usually also takes care of solid waste

management. At the national level, the Ministry of Forestry and Environment

(MFE) and the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) are responsible for

policies regarding solid waste.

1.6 Legal Aspects

Important laws and regulations with regard to solid waste are the National

Environmental Act, the Pradeshiya Sabha Act, and the Urban Council and

Municipal Council Ordinances. The Environmental Act restricts the emission

of waste materials into the environment, and states the responsibilities

and powers of the CEA. The local Government Acts and Ordinances state that

the local authorities are responsible for proper removal of non-industrial

solid waste, and for providing suitable dumpsites.

1.7 Life cycles

Organic waste consists of materials that will naturally degrade within

a reasonable time period. It can be composted or converted into methane

(biogas), and some of it can be fed to animals.

Paper and cardboard waste are essentially also a form of organic waste.

When to too dirty, they can be recycled or re-used (e.g. for wrapping,

as bags or envelopes, and for writing on the unused side). When dirty,

they could be composed, but caution may be needed because of the printing

ink.

Glass can be recycled, and glass bottles can be re-used. Other silicate

(stony) materials can be used in things like road construction, but might

first need to be grinded.

Most metals can be recycled. Care should be taken with dumping, as heavy

metals can cause serious pollution.

Plastics will degrade naturally, but only very slowly. Addition of certain

materials during production can speed up this process. Some types of plastic

waste (mostly PET, PE and PP) can be recycled mechanically, but will have

to be sorted and cleaned. Tertiary (chemical) recycling of plastics is

also possible, and can often handle more contaminated waste, but these

techniques are not yet widely available.

2. Methodology

2.1 Interviews

To get more insight into the workings and organisation of solid waste management,

interviews were conducted with national and local government agencies,

"town-cleaning" firms, waste resellers and local residents. The reliability

and completeness of the information obtained through these interviews might

in some cases be questionable, so care should be taken in its interpretation.

2.2 Collection survey

We accompanied a group of town cleaners on their morning shift, to gain

familiarity with their methods, to get an idea of the composition and amounts

of collected waste and to see which materials are kept apart by the cleaners

for reselling.

2.3 Dumpsite survey

The main dumpsites in Ja-Ela DS were visited and detailed observations

were made (see appendix IV). Quantitative measurements of any kind proved

difficult, so were not really performed. The size of the sites was estimated.

2.4 Measurement of waste production

Waste production and composition were measured for 15 households, half

of which were located in a more "rural" area (Delature), and half in a

more "urbanised" area (Ekala). The households were further divided into

two or three income groups. Waste was collected four times over three weeks,

sorted into several material types and weighed. Waste from some retail-shops

and eating-houses was also collected and analysed. The results obtained

are mostly indicative, as precision and representation of the measurements

leave something to be desired.

3. Survey Results

3.1 Waste production

The reliability of the figures is somewhat questionable, due to small sample-size

and large variation. Collection by the households might also have been

selective, leading to a slightly biased result.

Waste production of the households measured seems to be in the range

of 100-300 g per day, not including waste materials that were recycled

or re-used. Households in more rural areas often seem to use their organic

waste as animal feed (not necessarily for their own animals) or for composting.

The average composition of the household waste we measured (by weight),

seems to be roughly as follows: 15%-30% plastics, 30%-40% paper, 0-30%

organic fraction and 10%-30% rest-fraction. The plastic and paper fractions

make up most of the volume of household waste, but can be significantly

compressed. The organic fraction makes a relatively large contribution

to the total weight, due to its high density and water-content.

Packaging materials make up more than half of the plastic and paper

fractions, both by weight and by volume. A significant part of the paper-fraction

is already made of recycled materials. Only a small part (less than half)

of the plastic fraction would be easy to recycle mechanically. Most packaging

materials produced in Sri Lanka do not state the material type.

Restaurants and eating-houses produce a lot of food and kitchen remains,

which are usually collected by local pig farmers, who use it as animal

feed. Retail shops produce mostly packaging waste.

3.2 Waste collection

Some relevant information on the waste collection resources of the various

local authorities is listed in table 3.3. Cleaning of (main) roads and

markets has been recently privatised in Kandana PS and Ja-Ela UC, and seems

to function better than the former public cleaning systems.

Waste collection and cleaning is mostly paid out of assessment tax and

trade licences.

Frequent cleaning and collection of roadside waste is mostly restricted

to main roads and town areas. Cleaning of the roadside drains is included

in the duties of the local authority cleaners, but is currently insufficient.

The cleaners proceed along their daily route, sweeping and shovelling

up roadside litter and garbage (including a lot of sand and stones), and

throwing it in a tractor-trailer or handcart.

There seems to be an increasing tendency, especially among shop owners

and higher-income households on the town-edges, to use bags or bins, instead

of just dumping the garbage along the roadside. Centrally placed garbage

barrels, which are provided by the private cleaning companies in Ja-Ela

and Kandana, are also effective, although many barrels get stolen.

Plant material makes up a very large part of the collected municipal

waste. Estimates give around 60%-90% for the organic fraction (by weight).

3.3 Waste disposal

Households generally dump or burn their waste materials. Dumping is usually

done in a shallow pit in the ground, along the roadside, on a nearby dumpsite,

in low-lying marshland or in waterways or waterbodies. Dumped material

is often periodically burned.

Local authorities usually dump their collected waste on privately owned

land. Finding suitable sites is difficult, and current sites are therefore

often over-used. Officially, waste is not burned by the authorities after

dumping, but it does happen.

No regulations or guidelines have been made to govern dumping of solid

waste by private companies or industries. Uncontrolled dumping of (hazardous)

industrial waste and of slaughterhouse waste is problematic, and poses

a potential health risk. Other problems with disposal include smell, prolonged

exposure to noxious gases from the burning of waste, scattering of waste

materials, presence of potential container habitats and ingestion of plastic

bags by cows, pigs and other animals. Serious water pollution (mostly eutrophication)

was observed in a few places, but does not (yet) seem widespread. Measurements

are needed, however.

There do seem to be any usable laws or regulations that deal with unauthorised

dumping of non-hazardous solid waste. Sometimes the Nuisance Ordinance

is used by local authorities to stop undesired dumping.

3.4 Re-use and recycling

Especially households in more rural areas re-use organic waste as animal-feed

and/or for composting. Pieces of cloth are also sometimes re-used. In more

urbanised areas, re-use of waste materials seems virtually non-existent.

Town cleaners seem to keep several materials separate from the rest

of the collected waste. Especially corrugated cardboard, metal cans, scrap

metal, glass bottles, firewood and some food remains are re-used or sold

to waste buyers for recycling.

Waste buyers (re-sellers) often have small shops, where they buy, sort

and store things like (news)paper, corrugated cardboard, scrap metal, glass,

barrels, plastic containers, sacks and sometimes black-coloured plastics.

These materials are obtained from companies, town cleaners, house-to-house

collectors, scavengers and other individuals, and are either sold locally

for re-use or are sold to recycling-companies, usually through a middleman.

House-to-house collectors buy mostly (news)paper, glass and metal from

households, and sell these to the re-sellers at a small profit.

3.5 Public awareness and attitude

The results below might not be representative, because of the small sample

group and superficiality of the answers.

Many people do not seem aware of the (potential) environmental problems

caused by disposal of solid waste. Garbage is often only seen as a problem

because of practical reasons.

Most people seem to know about health problems (especially mosquitoes)

relating to garbage, from school education or media. The extent and depth

of this knowledge was not determined.

Waste materials that can still be sold or re-used are not seen as waste,

but as something which still has value. However, it is usually thrown away

when not collected.

Proper collection (and dumping) is seen by many residents as a solution

to garbage problems.

3.6 The role of the Government

Lack of resources makes it difficult for local authorities to do anything

about the waste problem other than clean the main roads. According to them,

the National Government should provide the necessary legislation and resources.

According to the CEA, waste management is a task for the local authorities.

The CEA have neither a license-system, nor any regulations, standards or

guidelines for solid waste disposal (except for some hazardous materials).

The relevant sections of the National Environmental Act have not been implemented.

Measures of National Government agencies to help solve the waste-problem

seem currently limited to some awareness-material, mostly for schools.

3.7 Future policy

The Ministry of Forestry and Environment is working on a National Strategy

for Solid Waste Management (NSSWM), aimed at municipal solid waste. A three-year

implementation plan has already been made. Responsibilities are to be shared

between national Government bodies (Ministries, the CEA, etc.), local authorities,

the private sector, and the general public. Implementation is co-ordinated

through committees at national, provincial and local levels. Details and

the matter of funding are still unclear.

Waste reduction is mostly envisaged through public awareness and regulation.

Re-use and recycling are to be promoted, partly through tax-measures. Properly

engineered landfills are to be set up on a regional level and are to be

shared between various local authorities.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Shown here is the full text of the chapter from the report, not a summary.

4.1 Main conclusions

General

-

The relation between weight and volume of household waste can vary greatly

with water content and the amount of compression, and is thus partly dependant

on methods of storage, transport and disposal. This means that some care

should be taken in interpreting figures that state weight or volume of

household waste, without giving additional information about water content

and/or density.

-

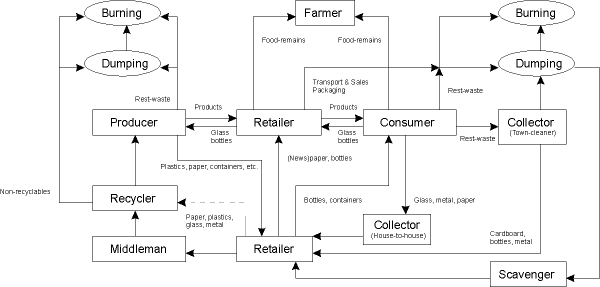

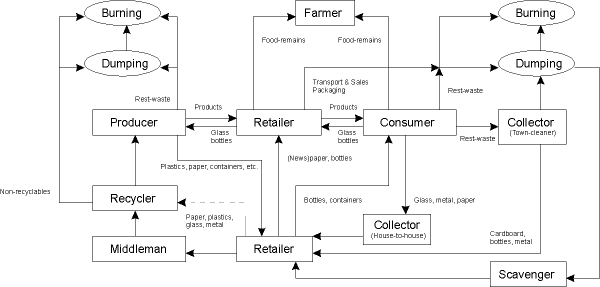

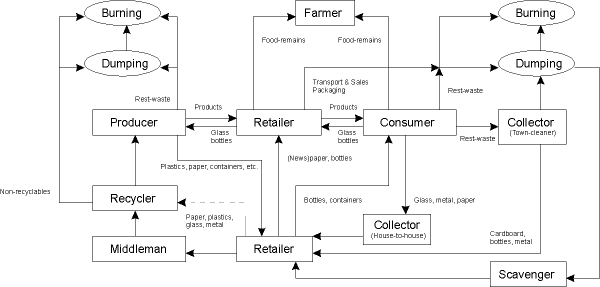

The main solid-waste streams in the Ja-Ela District can be depicted as

follows:

Figure 4.1 The main product- and solid-waste streams

in the Ja-Ela DS Division.

Institutional

-

Responsibilities of Government agencies with regard to solid waste management

(and the maintenance and cleaning or drainage channels) often overlap.

This leads most of the agencies involved to pass responsibility for solving

the problems to each other, without taking any action themselves.

-

Several parts of the National Environmental Act seem currently unimplemented

and/or not used, including the provisions for solid waste disposal.

-

There are currently no regulations, standards or guidelines for the disposal

of solid waste. There are only some guidelines for certain hazardous materials.

Waste production

-

Relatively little can be said about the waste production of a given household

based on its income and location.

-

The plastic and paper fractions of household waste make up most of its

volume, but the organic fraction often contributes the most to its weight.

This is mainly because of the high water-content of the organic fraction,

when compared to the other fractions.

-

Packaging waste makes up more than half of the paper and plastic fractions

of household waste, both by weight and by volume. In the case of the households

we measured, some 60%-80% of the plastic and paper waste consisted of discarded

packaging material.

-

The "municipal solid waste" as collected by town cleaners contains a lot

more organic material and sand/gravel/stones than the household waste that

was measured outside the towns. This is partly because the methods used

to collect the waste, which make that a lot of sandy material and leaves

from the roadside are included. It is also likely that not all of the organic

waste produced by households was measured. Gardening waste seemed largely

absent (and is possibly re-used in the garden), and selective collection

might also have played a role, making that the size of the organic fraction

was possibly underestimated.

Waste collection

-

Waste collection (or "town cleaning") involves sweeping and the removal

of waste from the roadsides. It covers mostly town areas and main roads.

Byroads are sometimes also cleaned, but less frequently.

-

Household waste is only collected when deposited along the side of the

road. Some households just dump it there, but especially shops and (higher-income)

households at the edges of towns are also starting to use garbage bins

or plastic bags.

-

The manner in which the roadsides are swept and garbage is picked up, makes

that relatively large amounts of leaves, soil, gravel and small stones

are included in the waste which is collected and subsequently dumped.

-

Privatisation of the collection / cleaning system seems to significantly

increase its effectiveness.

-

Cleaning and maintenance of roadside drainage channels is currently insufficient.

-

Possibilities to improve the efficiency of roadside waste collection include

promoting the use of garbage bags and bins, and placement of central barrels

or depots for disposal of household waste. The main problems are that barrels

are often stolen, and that bags inhibit the extraction of recyclable or

re-usable waste materials by town cleaners.

Waste disposal

-

Finding suitable dumping sites for collected waste poses a problem for

most local authorities.

-

Most dumpsites in the Ja-Ela District are located in marshy areas, especially

along the edges of Muthurajawela Marsh.

-

Although plastics make up a relatively small fraction of the dumped waste

(especially by weight), they do dominate the dumpsites because they do

not easily decompose (like paper and organic waste) and are not recycled

(like metal and glass waste).

-

Access to many dumpsites can be a problem, especially in rainy periods.

-

The majority of dumping sites may constitute a hazard to the public health

and to the environment. The dumped waste is not covered frequently, waste

materials (especially plastics) are spread by wind and water, and leachate

and runoff are free to reach ground- and surface water.

-

Solid waste disposal is also a problem for most industries, both large

scale and small scale. There are no facilities, no regulations, and in

most cases no guidelines or standards.

-

Uncontrolled dumping of slaughterhouse waste takes place at a fairly large

scale and constitutes a nuisance as well as a risk to the public health.

Re-use and recycling

-

Most households do not seem to re-use much. Bottles and containers are

often re-used, as are some plastic bags. Organic material is mostly used

as animal feed or compost in the more rural areas. But especially in urbanised

areas, re-use of organic materials is currently insufficient to non-existent,

and can easily be much higher.

-

Most paper and organic waste could theoretically be easily recycled, but

sorting and quality of the materials would be a problem.

-

Plastics are difficult to recycle and sort. Plastic waste contains a lot

of laminate materials and other composite products, and is sometimes very

dirty.

-

Contaminants, including heavy metals and other toxic substances, might

become a problem when organic material is re-used (by composting, or in

a biogas-digestor) on a larger scale.

-

It seems that in the current situation, a number of recyclable and/or reusable

materials are almost completely removed from the waste stream by the "informal"

circuit of waste collectors and resellers. The materials involved are mostly:

-

newspaper, books and plain paper (before re-use);

-

corrugated cardboard, when dry and relatively clean;

-

glass bottles and jars;

-

larger sized metal objects, sometimes also including cans;

-

food remains, in some (rural) areas and households;

-

gardening waste, in some (rural) areas and households; and

-

empty barrels and good-quality (plastic) containers of larger size;

-

The waste materials which are currently not collected for recycling, include:

-

paper and cardboard packaging;

-

newspaper and paper, after re-use;

-

plastic packaging and other plastic articles;

-

most composite materials;

-

organic waste (depending on the area and the household); and

-

hazardous waste, such as chemicals, oil remains, batteries, etc.

-

The "informal" circuit creates a significant amount of jobs, for collection,

buying and selling, processing and sorting, transport, and recycling.

Collection and/or re-selling of recyclable and re-usable waste materials

has a low profit margin, but can nevertheless provide a full income in

many cases.

4.2 Recommendations

Reduction

-

Measures for waste reduction at the source, should probably focus on reducing

the number of plastic bags provided at shops (or used by consumers), and

on reducing the amount of (plastic) packaging waste. Better alternatives

should be provided.

Recycling

-

Plastic packaging materials should be marked for material type, to ease

sorting for mechanical recycling. Many imported products are already marked.

-

Plastic products which might be suitable for recycling (and are relatively

easy to sort and clean) include cups (of yoghurt, ice, etc.), bottles (PE/PET),

pots and other containers (usually PE), and PE/PP packaging foil and bags,

although distinguishing between material types might be difficult.

-

The possibilities for tertiary recycling of plastics should be investigated

(see § 1.7).

Disposal

-

Properly engineered dumpsites are needed. At the very least, suitable locations

should be selected for new sites (which means that a suitability check

has to be performed).

-

The biogas-digestors which are being developed and tested at the National

Engineering and Research Department (NERD) in Ekala, could provide a cheap

and effective method for disposal (or at least reduction) of municipal

solid waste with energy recovery, as the organic content of the waste is

very high.

-

More research is needed into the effects of the current open dumpsites.

Some samples of groundwater and surface water in the vicinity of some dumpsites

should at least be taken and analysed.

Awareness and instruction

Proper awareness and instruction campaigns are needed on the effects

of the current solid-waste disposal practices, and on solutions for (some

of) the problems.

Awareness material and usage instructions for things like compost barrels

should be suitable for the entire target group intended. This is

currently not always the case, as most material produced is only suitable

for better-educated people who already have an interest in the subject.

If needed, various versions of the same material can be produced for different

target groups.

The channels used to distribute the message should also be able to reach

the entire target group. Newspapers are often only read by a small portion

of the population, and each newspaper has a slightly different target group.

Television is effective, but does not reach the lowest income groups. Radio

is somewhat less effective, but can also reach some people with lower incomes,

and especially people at work. Posters are usually the least effective,

but may gain something in effectiveness when put up at places where they

will be frequently and easily seen. Brochures can be very effective, but

are also expensive and difficult to distribute.

Usage instructions should give clear and short instructions, preferably

using additional illustrations. They should be written in simple and unambiguous

language, and should also include information on what not to do.

4.3 Suggestions for local action

As waste is seen more as a practical than as an environmental problem,

it will be difficult to mobilise community support for a participative

waste-collection and recycling programme. Most people feel that waste management

is a task for the Government, and would only be willing to take action

themselves if it yields sufficient benefit. Experiences with the Arthacharaya

community waste collection programme have already shown that financial

benefits from selling sorted garbage are fairly low on a household level

(IRMP, 2000). Therefore such a programme would only be effective in very

low-income areas, where even small benefits count.

The low benefits for selling waste materials are mostly caused by the

fact that one household does not produce much waste, and does therefore

not get much income from selling it. This problem is avoided if the benefit

is spread over fewer people. A house-to-house buyer for instance, can make

a living out of buying and selling waste materials from a number of neighbourhoods

(see § 3.4). His profit margin is low, but this is because the major

part of the financial benefit actually goes to the households!

To start a successful and self-sustainable community/neighbourhood waste-management

project, it would be most efficient to incorporate the informal collection

and recycling routes that already exist. This existing system of "informal

waste collection" can then be extended to include the waste materials that

are currently not (sufficiently) collected and/or recycled. When implemented

correctly, this could result in benefits for everyone involved (households,

collectors, resellers, recyclers).

In such a system it is absolutely essential to have the support of the

community. The households are the ones that have to initially sort and

store the waste materials that are to be collected for recycling. Therefore

to ensure co-operation, the local population must be involved in setting

up the system. It is very important that they are correctly informed on

proper sorting of waste materials, on composting and on management of household

waste in general. For most people, the incentive for co-operation will

probably be the fee for selling the waste (IRMP, 2000), and the fact that

waste is now properly collected (see § 3.5), so that it is no longer

their worry.

It would probably not be difficult to get support from waste buyers

and recyclers, as such a project would mean an expansion of their market,

by which they have something to gain. One potential problem might be that

they might get more competition, which (especially considering the nature

of the Sri Lankan society in this regard) might not always be appreciated.

The project would have to focus mostly on collection of paper and plastic

packaging materials, and on collection and/or local re-use (composting,

feeding animals) of organic waste (in areas where this is not already happening).

In a proper collection system, provisions also need to be made for the

rest-fraction and for hazardous waste (chemicals, etc.). This might pose

a problem, as no profit can be obtained from collection and disposal of

these fractions, and these activities will have to be funded somehow.

The local residents should be briefed in a workshop on how to sort waste

and make compost, and also on what not to do. This last point is

very important, and can help to avoid many problems. This is often forgotten:

instruction briefings for many projects only seem to focus on what to do,

but not on what to avoid.

Expected problems include the following:

-

Lack of space for storage, especially among low-income households,

and in more urbanised areas. Collections will have to be more frequent

(which will result in decrease of benefits for the collector), or other

provisions need to be made. Central storage could be considered, but is

impractical and involves extra cost.

-

Lack of space for composting, or no use for compost. In this case

organic waste will have to be collected for composting by someone else,

for biogas production or for animal-feed. This might be a problem, as storage

of organic waste is near to impossible, due to smell and animals.

-

Animals. Especially dogs, cats and crows will often go through waste,

looking for something to eat. This may cause the (sorted) material to be

scattered again, and will make (storage for) collection very difficult.

The animals are usually able to open plastic bags, so these offer no protection.

A (heavy) bin would help, but will involve extra costs.

-

Improper sorting. For many people it is difficult to distinguish

between waste-types, even with proper instruction. Also, quality of the

waste is of importance. Dirty paper should for instance be deposited with

the organic fraction or the rest-fraction. Very dirty plastics are difficult

to clean and recycle, so should also go with the rest-fraction. The organic

fraction often contains small bits of plastic, which are difficult to sort

out. If the waste materials are improperly sorted at the household level,

the quality (and with it the value) will go down.

-

Plastics. For (mechanical) recycling, plastics will have to be cleaned

and sorted to material type. This will involve extra costs, which might

outweigh the benefits, except when done by volunteers. Sorting plastic

types is also very difficult, as most locally produced packaging materials

are currently not marked.

An alternative would be to only recycle product types that are easy

to sort, to clean and to recycle. Things like plastic bottles, yoghurt

cups, etc. The rest would have to be dumped, or burned at elevated temperatures

(for which no installation seems to be currently available in Sri Lanka).

Tertiary recycling (see § 1.7) is also an option, but the technology

for this might not yet be available in Sri Lanka or around.

-

Residual waste. As was already mentioned, collection of these (usually

non-recyclable) waste fractions will involve extra cost (except when done

by volunteers - perhaps schoolchildren). The rest-fraction would have to

be dumped or burned. It is likely that there are currently no proper facilities

on the island to dispose of hazardous materials (chemical residues, batteries,

etc.) in residual household waste.

Meat remains are best not composted, so these will go into the rest-fraction.

However, this will make it more difficult to store, because of smell and

animals.

Besides the sort of larger-scale community project suggested above, initiatives

for waste collection and recycling are also possible on a smaller scale,

and for a more limited target group. An example of this could be the following:

Hotels and restaurants, especially in tourist areas, produce a significant

amount of plastic (PET) drink bottles. These are relatively easy to collect,

store and clean, and also easy to recycle mechanically. Therefore, it might

be useful to set up a kind of bottle-collection system for hotels, restaurants

and guesthouses in the Negombo area. Hotels and guesthouses could have

a separate bin in which tourists can deposit PET bottles. This would be

good for the "environmental" image of the participating hotels, restaurants

and guesthouses, and might also provide some positive publicity for IRMP.

4.4 Comments on the NSSWM

The proposed National Strategy for Solid Waste Management is fairly complete,

in that it covers the entire waste-cycle from production (avoidance) through

re-use, collection, recycling to disposal. This is done in a fairly integrated

manner, and according to the established hierarchy of waste management.

In the light of this report however, a few notes need to be made on the

strategy:

-

Some practical aspects of the proposal are still very vague. For example,

the motto of "reduce, re-use and recycle" is one of the pillars of the

plan. But nowhere is it mentioned which kinds of products might

be re-used (for instance containers, bottles and plastic bags might be

possible candidates). The measures for waste reduction on the consumer

side are also somewhat unclear. But more importantly, it is still not fully

known where the initial money for implementation of the plan has to come

from.

-

The proposal does not consider the fact that many materials are already

being sorted out of the waste stream for re-use and recycling, by the "informal"

circuit (see § 3.4). Integration of the existing informal systems

into the proposed collection system might somewhat simplify implementation

of segregated waste collection.

-

Practical problems with collection and with sorting of waste at the household

level are not considered. See paragraph 4.3 for examples. Especially

storage of waste will be a problem for many households.

-

The plan only targets municipal solid waste. And more importantly, through

the proposed methods of sorting, composting and awareness building, it

implicitly targets mainly better-educated and higher-income households

located in more urban areas. This is not really a problem, as this group

is the easiest to start with, but nowhere is this explicitly mentioned.

It is however an important realisation, as it implicitly limits the initial

scope of the plans for segregated waste-collection. It means that low-income

and poorly educated families, and households in more rural areas will or

can not easily be included in the waste-collection and recycling schemes.

At least, not at first. In other words, the majority of households in the

country would initially not be covered by the measures proposed in the

strategy.

And finally of course, as is the case with all proposals: The plan

looks good, but it is always the question if it can and will be implemented

properly. The proposed three-year timeframe sounds good, but may be a bit

optimistic considering previous experiences.

References

| CEA |

Central Environmental Authority of Sri Lanka |

| GCEC |

Greater Colombo Economic Commission |

| IRMP |

Integrated Resources Management Programme in Wetlands |

| NL |

The Netherlands |

| WCP |

Wetland Conservation Project |

Abracosa, Ramon

Philippines Urban and Industrial Environment

http://www.aim.edu.ph/rpa/papers.htm

(Note: document no longer available online)

Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

National Environmental Act No. 47 of 1980,

incorporating Amendment Act No. 56 of 1988

(CEA consolidated reference copy)

http://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/srl13492.pdf

http://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/srl13496.pdf

Free University of Amsterdam (NL), Dienst VEB, Januari 1999

M. Aarts, G. Beernink, C. Evenhuis, J. Grant, F. Henriquez,

L. van Hulst, A. Kreleger, E. Krijger, K. Ooteman,

H. van den Os, M. Stomp, M. Zeeman, L. van Zon

Wetenschapswinkel report no. 9901

A qualitative and quantitative comparison of the German and Dutch

Government policies on packaging waste

http://environmental.scum.org/packaging/

GCEC, Euroconsult NL, March 1991

Environmental Profile of Muthurajawela and Negombo Lagoon

Independent Newspapers, South Africa, 1999

Putting plastics in litter perspective

http://www.saep.org/forDB/forDB9906/WASTEplasticsARG990604.htm

(Note: document no longer available online)

IRMP Technical Report No. 1, December 1998

P.K.S. Mahanama

Socio-Economic Baseline Survey in Muthurajawela

IRMP, January 2000

Charlie Austin, Shashikala Ratnayake, Nalaka Siriwardena

Evaluation of Arthacharaya's Community Waste Management Project

in Negombo

IRMP, June 2000

Levien van Zon, Nalaka Siriwardena

Project Proposal: Data Collection on Solid Waste Management in the

Ja-Ela Area

Ministry of Forestry and Environment, Sri Lanka, 1999

Database of Municipal Waste in Sri Lanka

Ministry of Forestry and Environment, Sri Lanka, August 1999

National Strategy for Solid Waste Management,

Narmathaa Group, Interplamak Plastic Packs (India) Pvt. Ltd.

Bio-degradable polyethylene film

http://www.narmathaa.com/bio-inter.htm

(Note: document no longer available online)

Raabe, Robert D.

Berkely University (USA)

The Rapid Composting Method

http://commserv.ucdavis.edu/ceamador/rapidcompost.htm

Note: original link is outdated, this document can now be found here:

http://ucce.ucdavis.edu/files/filelibrary/40/963.pdf

Randall Curlee, T., and Sujit Das

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (USA), September 1996

Back to Basics? The Viability of Plastics Recycling By Tertiary

Processes

http://www.yale.edu/pswp/

Schall, John, October 1992

Does the Solid Waste Management Hierarchy Make Sense?

A Technical, Economic & Environmental Justification

for the Priority of Source Reduction and Recycling

http://www.yale.edu/pswp/

(c)2000-2003, Levien van Zon (levien @ scum.org)